Decreasing tax revenue to harm Vietnam’s sustainable development: Expert

Vietnam could get rid of its most large tax incentives without harming its growth or competitiveness, said an Oxfam expert.

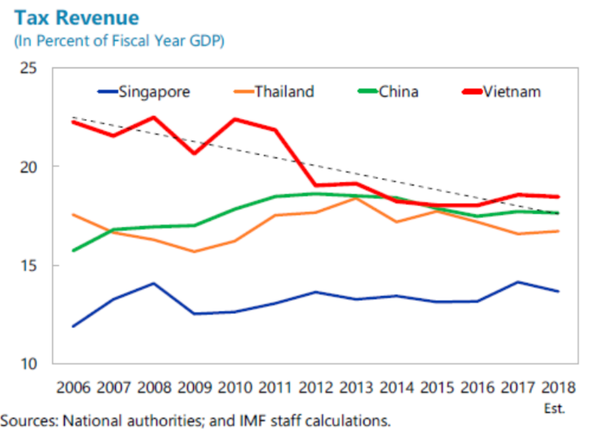

Compared to the size of the economy, tax revenues have been decreasing over the past years in Vietnam. On the long term this could harm the sustainability of the country’s economy, according to Johan Langerock, tax policy expert at Oxfam.

| Oxfam's tax policy expert Johan Langerock. |

“Vietnam’s extraordinary economic track record has not been accompanied by a similar pathway in tax revenues,” said Langerock at the Vietnam Fiscal Policy and Development Forum 2019 on November 13.

On this issue, Nguyen Thi Thu Huong, senior program manager – governance of Oxfam in Vietnam, said tax revenue decreased from 27.3% of GDP in 2010 to 23.7% in 2016, while revenue from corporate tax went from 6.9% of GDP in 2010 to 4.3% in 2017.

“This situation puts growing pressure on Vietnam,” stated Huong.

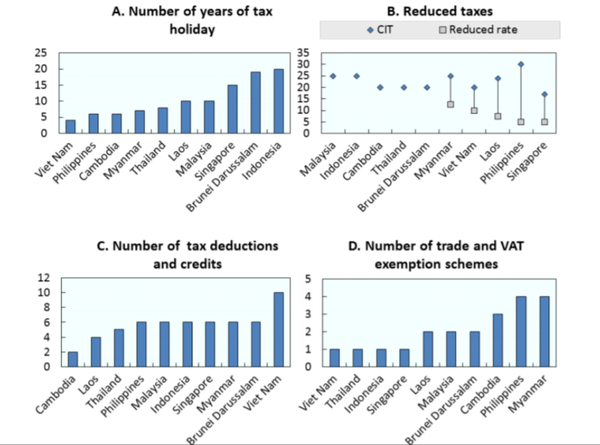

In the 2012 – 2016 period, Vietnam’s combined tax incentives for enterprises are equal to 7% of total state budget revenue and 5% of the country’s total expenditures.

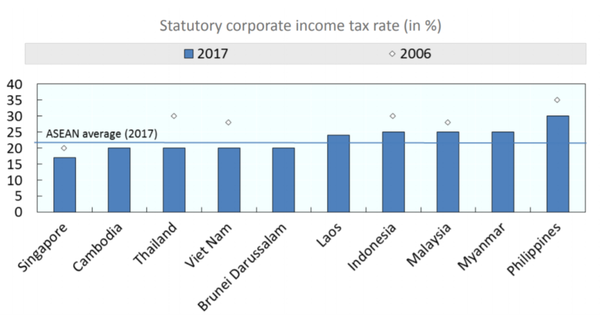

One of the main reasons for a decrease in tax revenues is the reduction of corporate income tax rates and the existence of many tax incentives for foreign investors, said Huong.

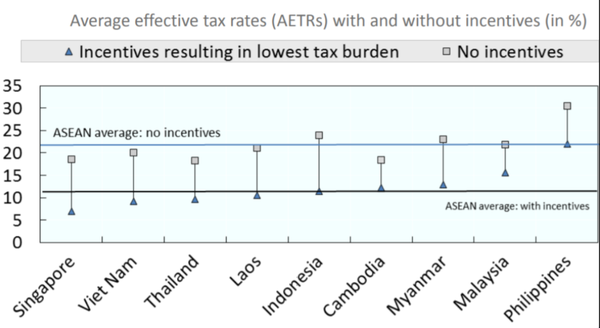

In 2016, the actual tax rate for these companies was 10%, less than half of the common tax rate of 20%, Huong pointed out.

“So while tax revenues were decreasing, tax expenditures have remained high,” Huong said.

| Source: Oxfam. |

Oxfam’s expert Langerock noted such trend is worrisome for several reasons. Most importantly, it means that the tax system is failing to capture and redistribute all the created income and wealth in the country.

According to Langerock, several reports have already indicated that the benefits of economic growth in Vietnam are increasingly accruing to the richest 10% of the population.

As a result, the export-led industrialization has developed significantly, at the expense of agricultural and small business development.

Necessity to rationalize tax expenditures for big companies

It is obvious that tax expenditure policies have contributed to the country’s economic growth by boosting investment. However, it is high time for Vietnam to rationalize its tax expenditures for big companies, stressed Langerock.

| Source: Oxfam. |

“Until today, the Vietnamese authorities have not been paying enough attention to analyzing the efficiency and effectiveness of its tax expenditure policies,” he said, adding the social cost of tax expenditures is too large to be further ignored. According to the OECD, the revenue loss is estimated at 1% of GDP, meaning a staggering amount of over VND50 trillion (US$2.15 billion).

This amount could potentially finance 25 new 1,000-bed hospitals in Vietnam. When tax revenue collection on large companies decreases, pressure to levy higher VAT on ordinary citizens increases or less public services are delivered.

| Source: Oxfam. |

Langerock stressed Vietnam could get rid of its most large tax incentives without harming its growth or competitiveness.

According to a recent survey by Grant Thornton on private equity prospect in Vietnam, 69% of the replies consider the rising of disposable income and middle-income class the most important factor for investing in Vietnam; 60% consider high and stable economic growth and only 13% consider government incentives and subsidies the most important factor.

Langerock added the problem unfortunately is not only at national level. At the moment, ASEAN countries are pushing each other into an aggressive race to the bottom in corporate taxes. Companies in the region have seen their tax rates paid lower over the last decade. Only large companies and wealthy shareholders win in such an environment at the expense of essential public services for ordinary citizens.

Langerock recommend Vietnamese authorities proceed in two ways. As a first step, some tax incentives should be eliminated after an impact assessment. Secondly, as the chair of ASEAN in 2020, Vietnam should put the issue on agenda to raise awareness and debate the issue of tax competition and tax incentives at regional level.

Both steps should lead to an increase in tax revenues in a fair and equitable way. Inequalities will decrease and the government will have more resources to invest in health, education and the fight against climate change.

“Vietnam can be a leader in tax reform,” asserted Langerock.