Health Diplomacy: A Cornerstone of the Relationship between the United States and Vietnam

0

On September 2, 1945, President Ho Chi Minh read the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence in the Ba Dinh Square and spoke about the values of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. At that time, the United States and Vietnam shared a common enemy: malaria. Our shared values, as demonstrated in our two Declarations of Independence and this public health problem, brought us together. Seven decades later, health diplomacy remains a cornerstone of our relationship.

Nearly 14,000 kilometers away at around the same time, military trainees and civilians in the United States were nearing the end of their own fight against malaria, thanks in part to the Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA) program. MCWA, launched in 1942, was designed to prevent malaria using a multi-disciplinary, collaborative approach. By 1945, the US government recognized the success of this disease control model and decided to apply it to other public health threats. On July 1, 1946, the Communicable Disease Center, or CDC, replaced MCWA and officially opened in Atlanta, Georgia.

In July 1950, a CDC team of experts in malaria control traveled from Atlanta to Hanoi to share information and experiences with their Vietnamese counterparts. The partners visited Ha Dong, Phung Khoang, Van Phuc, Thach Bich, Hai Duong, Van Quan, Ha Tri, and Phuong Tri and worked together to establish a regional malaria control program consisting of experts in epidemiology, mosquito surveys, and mosquito control.

Vietnamese and American partners trained provincial and local staff, who then went on to train additional staff, using a system now known as “cascade training.” This technical collaboration—less than five years after the Declaration of Independence of Vietnam and just one year after the establishment of the CDC—is, to our knowledge, the earliest contribution to what we now call “health diplomacy” between our two nations.

Just three years after the establishment of diplomatic relations between our two countries in 1995, health diplomacy became a way forward for cooperation and collaboration. CDC, now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, established an office in Hanoi in 1998 and another in Ho Chi Minh City in 2005. Together, CDC and the Ministry of Health agreed that HIV and tuberculosis prevention and control should be the first areas of focus for collaboration between Vietnamese and American health experts, bringing together multiple disciplines—just as malaria had in 1950—such as epidemiology and laboratory science.

An outbreak of avian influenza in Vietnam in 2003 provided another chance to strengthen our collaborations, allowing CDC to jointly identify new influenza viruses in live bird markets. The year 2004 saw the arrival of the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, bringing CDC, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Department of Defense together to support Vietnam, and our two countries made great gains in controlling HIV and tuberculosis, while our influenza partnership helped to prepare for the next influenza pandemic. This work fostered mutual respect, trust, and friendship, and laid the foundation for even broader cooperation down the road.

In 2013, CDC and Vietnam’s Ministry of Health collaborated on a project to demonstrate, in a short period, that additional financial investments and technical collaboration could further enhance Vietnam’s preparedness for major outbreaks. When that succeeded, we expanded our health partnership under the framework of the Global Health Security Agenda, or GHSA which, like PEPFAR, was also implemented in collaboration with USAID and the Department of Defense. The Governments of Vietnam and the United States worked together to strengthen surveillance for familiar diseases like dengue fever and measles as well as new ones like the Zika virus.

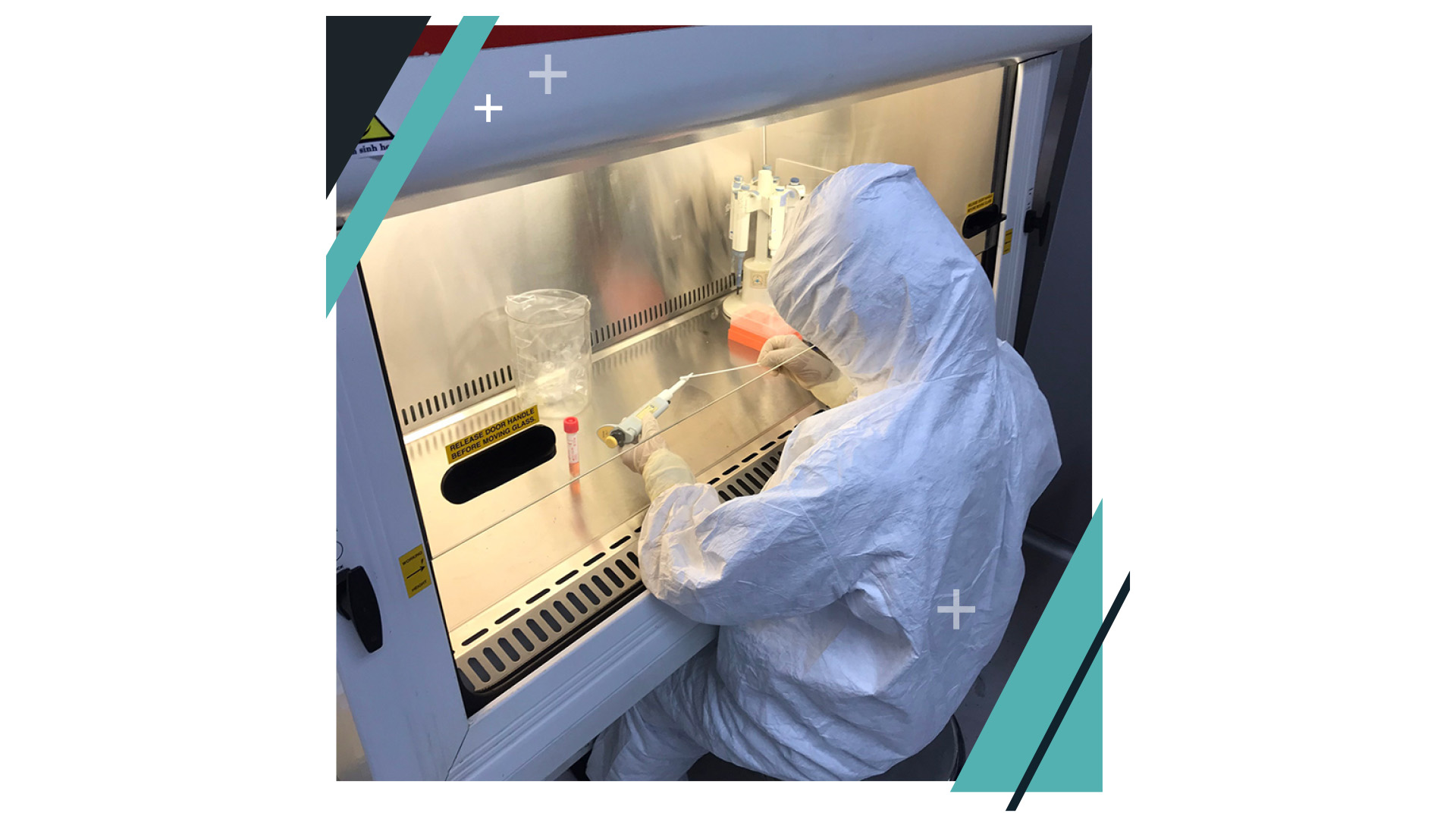

Over the next four years, we established emergency operations centers—hubs of epidemic intelligence—at the national level and in each of the four public health regions. We worked together to strengthen laboratory capacity and safety so that the most advanced techniques could be used to identify novel infectious diseases. We identified strategies for protecting hospitalized patients from preventable infections. We helped further strengthen the already robust, existing capacity in field epidemiology. We also worked to implement influenza vaccination for healthcare workers and to strengthen the program for routine childhood immunizations. Our work was preparing us for the greatest public health challenge in a century.

On January 8, 2020, Vietnam’s Ministry of Health invited CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO), another critical and trusted partner, to discuss a cluster of cases of respiratory infections caused by a novel coronavirus that had been reported in China.

The meeting was attended by leaders from all of the major departments of the Ministry of Health, but introductions were not necessary thanks to the workshop participants had been doing together for several years. Less than three weeks later, the first cases of the novel coronavirus were detected in Ho Chi Minh City and Nha Trang, and about one week after that, the Government of Vietnam established the National Steering Committee for Prevention and Control of COVID-19. This critical step provided a mechanism for different sectors of Vietnam’s government to work together, collaborate, share information, and provide leaders with the latest information.

Some of Vietnam’s actions at the beginning of the pandemic seemed drastic at the time. For example, the lockdown of Son Loi commune, home to 10,000 people in Vinh Phuc province, was quite unexpected. At a meeting of the National Steering Committee, Minister of Health Nguyen Thanh Long asked us to try to understand this approach. We listened and we learned. For good collaboration, it is important to understand the decisions that our partners make.

With this mindset of mutual respect and understanding, CDC has been proud to work with Vietnam in so many areas of the COVID-19 pandemic response. We have provided technical support on surveillance and diagnostic testing guidelines that will allow experts to identify new variants quickly. We have supported field investigations in Hanoi, Vinh Phuc, Ho Chi Minh City, Binh Thuan, and Hai Duong.

When Bach Mai Hospital experienced an outbreak of COVID-19 in March of 2020, CDC provided technical support to the investigation, to assess the ventilation, and to suggest strategies to prevent future spread. Today, we are collaborating with the Ministry of Health to study the spread of the virus in communities, and we are supporting monitoring for adverse events related to COVID-19 vaccination so that any vaccine-related problems can be identified and addressed quickly. And we are not doing this alone. With outstanding collaboration with our colleagues from WHO, USAID, the Department of Defense, and virtually all sections of the US Embassy, we are doing everything we can to support the people of Vietnam in this fight. Việt Nam ơi, cố lên!

When we think back to the CDC scientists who traveled to Hanoi in the summer of 1950, and we look at the future of Vietnam - US health cooperation, we feel nothing but optimism. We now have a long, shared history of two-way collaboration, and this has helped strengthen the relationship between our countries. This is the essence of health diplomacy. We look forward to Vietnam’s plans to establish its own CDC-like organization at the national level, and our CDC hopes to leverage our shared history and friendship for providing targeted support for the betterment of the Vietnamese and American people.

Eric Dziuban, MD, DTM, CPH, FAAP, Country Director, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hanoi, Vietnam Matthew R. Moore, MD, MPH, CAPT, USPHS, Director, Global Health Security Program, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Hanoi, Vietnam |