Is waiting 1-2 minutes at a red light really too much for us to take?

This week’s Words on the Street asks: Is a minute or two of patience too much to bear, or is the problem deeper – woven into our habits and shared spaces?

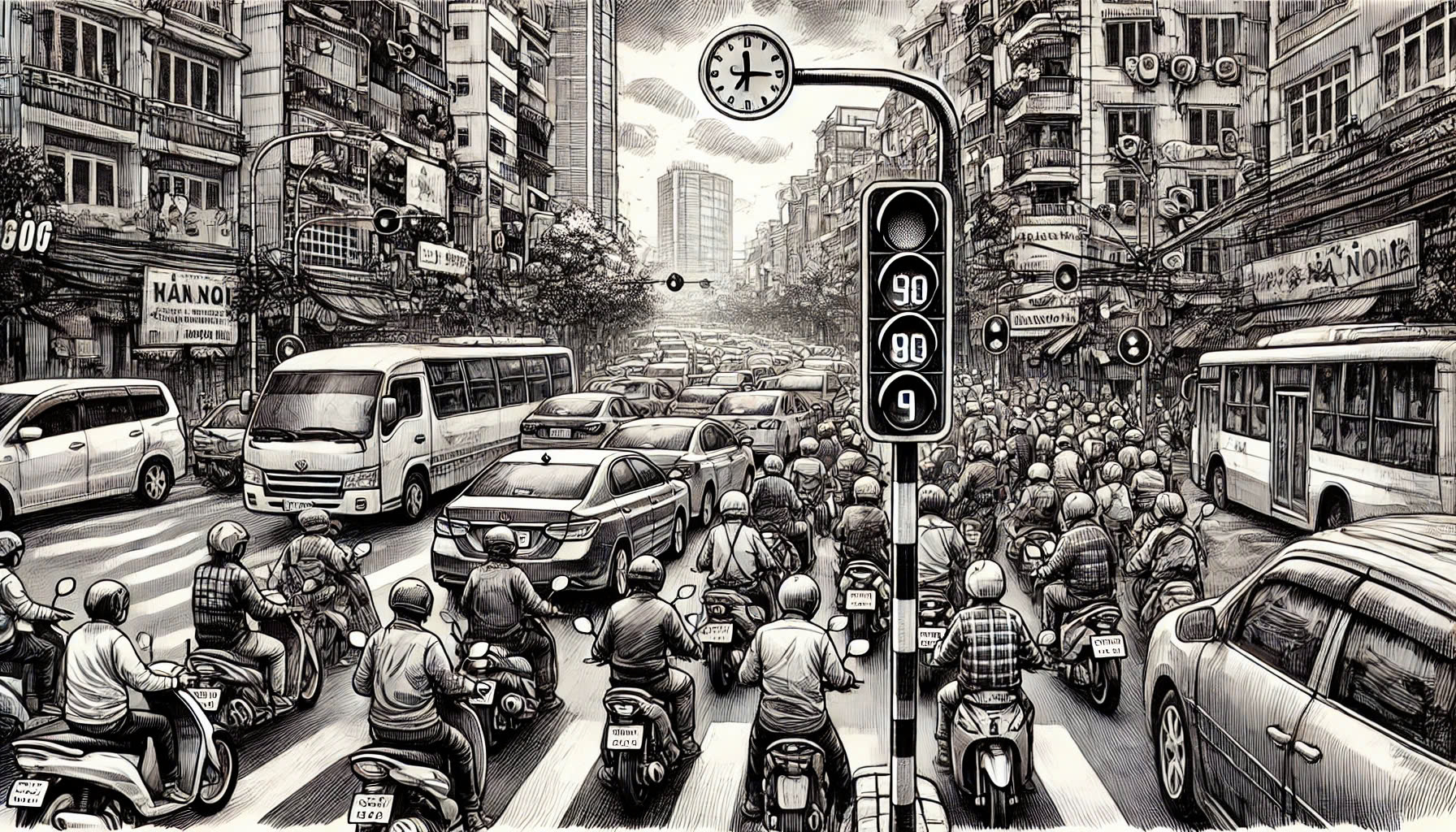

In Hanoi’s bustling streets, where traffic is both a daily routine and a constant challenge, even waiting at a red light sparks debate. As the Lunar New Year rush peaks, this week’s Words on the Street asks: Is a minute or two of patience too much to bear, or is the problem deeper – woven into our habits and shared spaces?

Over the past two weeks, traffic congestion in Hanoi and other major cities in Vietnam has spiked dramatically. Some have pointed fingers at the long red light durations at intersections, arguing that extended wait times force vehicles to waste too much time navigating busy junctions.

In other words, many road users believe the transportation authority should bear the primary responsibility for the worsening urban traffic. But is the blame entirely theirs to shoulder?

Take, for instance, the intersection of Dai Co Viet, Xa Dan, Le Duan, and Giai Phong – a major crossroads that sees one of the highest traffic volumes in Hanoi. To mitigate congestion, the Kim Lien underpass was opened in 2009, allowing vehicles traveling along the Dai Co Viet-Xa Dan axis to bypass the Le Duan-Giai Phong axis.

For left-turning vehicles from Dai Co Viet and Xa Dan into Le Duan and Giai Phong, the wait at red lights can stretch to 120 seconds. This delay prioritizes the heavier traffic flow along Le Duan and Giai Phong.

Under normal circumstances, most drivers and riders patiently abide by the signals here. So why is this an issue now?

There are several key reasons. First, traffic volume in Vietnam's major cities typically surges before the Lunar New Year as people rush to travel, shop, and visit family.

This seasonal spike overwhelms the existing infrastructure, unable to handle the sudden influx of vehicles.

Second, Vietnam’s "queue culture" remains weak. A quick glance at any busy street reveals a common scenario: vehicles weaving through every available space, adhering to an unspoken "fill the empty space" philosophy.

On wide roads with three or four lanes, cars frequently fan out into five or six, leaving motorbikes with minimal room to maneuver. This behavior not only frustrates motorbike riders but also underscores a deep-seated lack of courtesy and discipline among drivers.

Until road users learn to yield, prioritize the common good, and stop focusing solely on personal gain, Vietnam’s streets will remain gridlocked. As the saying goes: “Even if Hanoi had ten-lane roads, it’d still be jammed.”

Adding to the tension, some blame recent government regulations for exacerbating the situation. Effective January 1, 2025, Decree No.168/2024/ND-CP significantly raises fines for traffic violations. Many believe this has contributed to congestion, albeit indirectly.

I’m reminded of a saying my driving instructor shared over a decade ago: "When the light’s green with three seconds left, slow down to stop; when it’s red with three seconds left, get ready to go." This mantra was once a safety guideline.

Over time, however, it’s been turned on its head. Drivers now rush to beat the last three seconds of a green light, and rev their engines to jumpstart the moment the red light nears its end.

This reckless behavior often leads to collisions in the middle of intersections, creating prolonged gridlocks. The sight of vehicles stuck for hours is no longer uncommon in Hanoi.

Since the enforcement of Decree 168, many drivers have refrained from racing through yellow lights or edging past red lights for fear of hefty fines that can reach VND20 million (US$787.40) – equivalent to one or two months’ salary. The fine may go up to VND70 million ($2,756) if their violations cause severe property damages and loss of lives.

While this cautious approach has led to brief traffic delays as drivers stop more frequently at signals, isn’t it better to wait an extra minute or two than to be stranded in gridlock for hours?

The pre-Tet period is always a challenging time for traffic management. The collective mindset seems to be: “I don’t want to be on the road, but I have no choice.” Everyone rushes to wrap up errands, reach out to their social and business relationships, visit loved ones, and prepare for the new year, unwittingly overburdening urban infrastructure.

Are the authorities aware of these issues? Undoubtedly. Do they want to improve the situation? Absolutely. No traffic police officer or traffic inspector relishes standing on the streets all day to manage chaos. Decree No.168 serves only one purpose, which is to restore order and rebuild a long-lost culture of urban traffic discipline.

With infrastructure struggling to keep pace with population growth, the only immediate solution is to foster better driving habits. Drivers must stay in their designated lanes and resist the urge to create six car-wide rows on roads designed for four.

They should leave room for motorbikes and show courtesy at intersections. If we can embrace patience and mutual respect, waiting one or two minutes at a red light won’t seem like an unbearable burden – and we’ll avoid the much greater frustration of being stuck in gridlock for hours.