[Uniqueness of Hanoi's craft villages] Hanoi artisans strive to preserve traditional craft

Thanks to the efforts of the artisans of Xuan La village, the unique folk toys of To he still bring joy to many Hanoi children today.

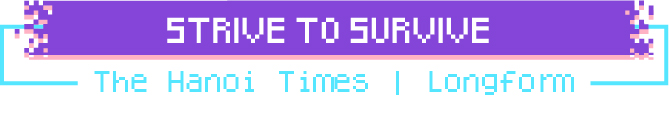

The colorful sophisticated rice flour figurines made by skilled craftsmen from Xuan La Village on the outskirt of Hanoi draw the attention of not only children but also adults who visit Hoan Kiem Pedestrian Street on the weekend.

Dang Xuan Anh, a To he-making artisan from Xuan La was delighted that Hanoi is returning to a normal rhythm of life as the pandemic situation is improving. He dyed glutinous rice powder in various colors, prepared a small comb, a bunch of sticks, and a spongy box to display his products, ready to take them to the Hanoi center for doing his family’s trade as soon as permission is given.

“I have lost a significant source of income for almost two years due to the Covid-19 pandemic,” he said, hoping the capital's festivals and entertainment activities will be allowed to resume soon.

This means that the income of Xuan Anh as well as other villagers from Xuan La will soon be improved. Making traditional toys out of rice paste not only gives the craft village’s residents an extra income when they are between rice crops, but also the chance to travel all over the country.

Being the eighth generation of a To he making family, Dang Xuan Anh is one of the many residents of Xuan La village who has mastered the art of shaping To he- rice paste toys.

Xuan La, 28 km south-east of Hanoi in Phu Xuyen District, has been producing these toys for nearly 300 years. And this traditional craft village is the only place in Vietnam specializing in handmade rice toys.

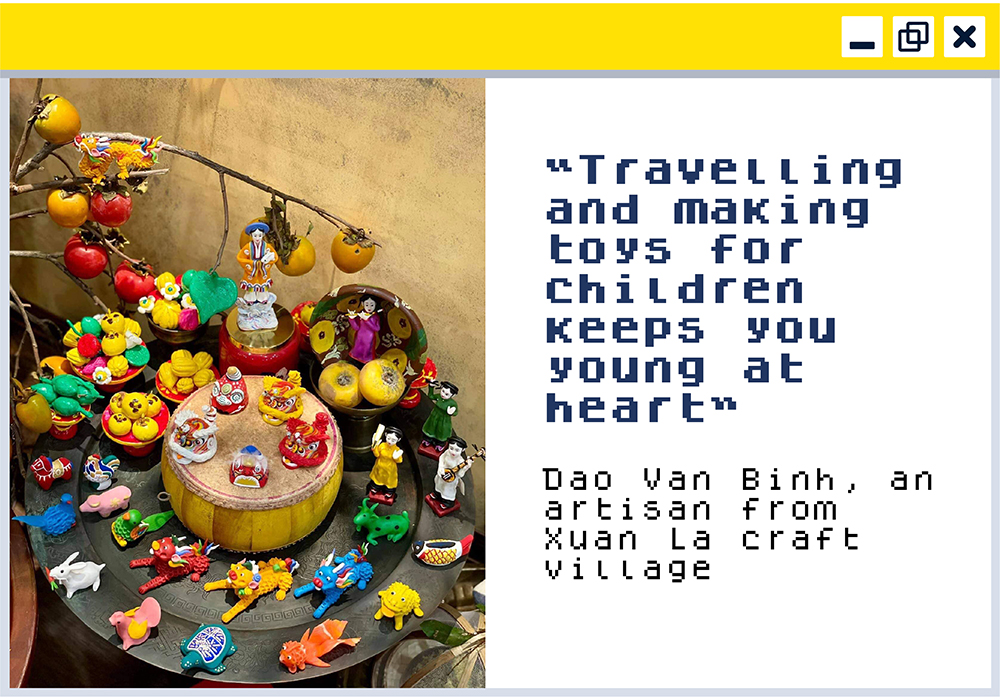

Rice-paste figurines were originally produced as offerings for pagodas and temples, but over time they became prized as simple toys for kids as well.

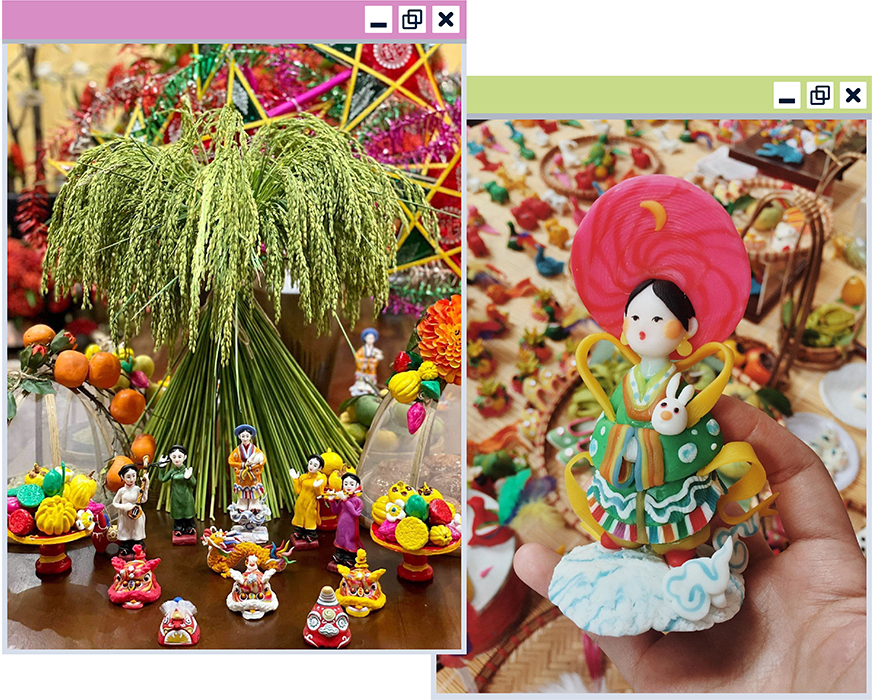

With simple tools To he artisans can knead many shapes of toys thanks to their skilled hands and creativity. Wherever a To he artisan appear on the street, he not only draws the attention of children but adults as well who enjoy waiting and looking at the way beautiful flowers, funny animals, or popular cartoon characters are gradually created.

To he is made from a paste consisting of equal proportions of glutinous and ordinary rice that is soaked for two days, pounded into a dough, dyed (mostly by floral material for safety, as the children may try to eat the To he), steamed, and then kneaded into balls.

The finished toys look fragile, but they are actually quite solid due to precise timing during the steaming stage, so the paste is neither raw nor overdone.

“Once I dropped my basket on the bus but none of the toys were broken,” said Xuan Anh. Rather than only creating the finished toys, some craftspeople just prepare the dough, take it to market, and make toys to order.

A skilled artisan can turn out a flower, a bird, a hero, or a mandarin in only a few minutes. Oddly enough, ready-made toys are cheaper, even though they are more complicated to make. Buyers pay VND20,000 (US$0,8) to VND25,000 ($1) to wait and see their order being made up, but the pre-made toys only cost VND10,000 ($0.4).

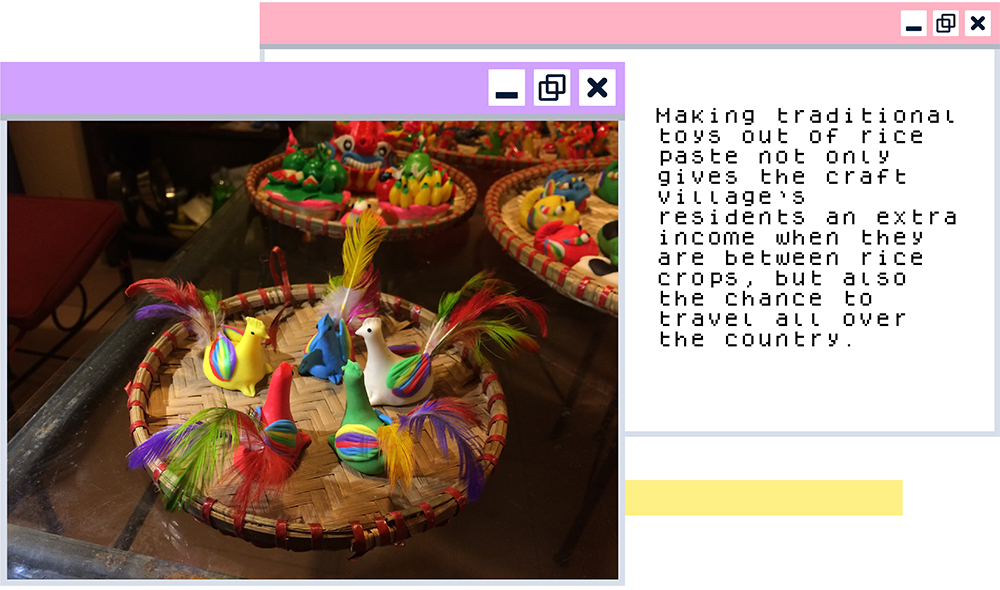

With a basket full of toys and a big lump of raw dough, Dao Van Binh, another artisan from Xuan La craft village, travels into the city. If he is lucky and his toys are in demand, he may only be away for one day.

Otherwise, he will have to stay at a guesthouse until all the toys are sold out. But Binh quite enjoys having to spend a night in the city. Like his fellow villagers, he appreciates the fact that the trade gives him the chance to travel.

Binh confided that “traveling and making toys for children keeps you young at heart”. It explains why there are more than 200 households from the village traveling all over the country, making To he.

“It’s neither an easy nor a hard job. But it requires a skillful hand and good taste to shape a figurine just a little bigger than a thumb carrying vivid feelings and expressions,” said Xuan Anh.

In Xuan La virtually everyone, from small children to old men, sculpt rice pastes into shapes. That only takes a couple of months of practice, but making the paste takes more skill. In less than five minutes, Xuan Anh can produce a colorful horse as requested by a client.

According to Binh, just before the pandemic, the people of Xuan La have been selling their wares to festivals all over northern Vietnam for years. Their busiest times, by far, are the mid-autumn festival and lunar New Year.

“My family only gets two days to enjoy Tet,” said Binh. “On the third day, we head off to festivals that are held all over the country in the spring.

But even when it is not the festive season, the villagers still take their wares to the city on the weekends, setting up shop in Hoan Kiem Lake Pedestrian Street, parks, or by the lakes. It’s a trade that seems to keep everybody involved perfectly content, even though it’s just a side job in their leisure time.

According to Binh, To he craft can generate remarkable income for the craftsmen, each of whom could earn an average of VND500,000 ($22) a day.

There are many people from the neighboring villages and even art students who come to the village to learn the trade, promising a brighter future for the craft village.

However, Xuan La craft village experienced many ups and downs as To he is facing fierce competition from foreign toys, particularly those made in China, which are much cheaper and diverse in designs and colors.

To he making cannot be widely practiced largely due to its traditional ingredient; rice powder makes it easy for the craftsmen to knead but on the other hand, it causes the toy’s appearance to quickly get moldy, dry, and split. A To he product can only be kept for couple of days depending on the craftsmen’s skill and weather condition.

At present, To he artisans hope to receive support from relevant agencies in terms of development orientation as well as from scientists to find an advanced material for To he making, in a bid to preserve and uphold one of the rare traditional trade of Hanoi.

![[Uniqueness of Hanoi's craft villages] Trach Xa villagers: Born to be skillful 'ao dai' tailors](https://cdn-media.hanoitimes.vn/2021/10/23/ao_dai55555.jpg?w=480&h=320&q=100)